Balalaika: Exploring Russia’s Iconic Triangular String Instrument

Balalaika is a string instrument from Russia. It is shaped like a triangle, and has just three strings. Not six like a guitar. Just three. But that’s all it needs. The sound it makes? Bright. Snappy. A little twangy. You can’t help but tap your foot when you hear it.

The body’s made of wood, usually spruce or maple, and the neck has little metal lines called frets. It’s tuned to E-E-A, which gives it that zingy, playful feel.

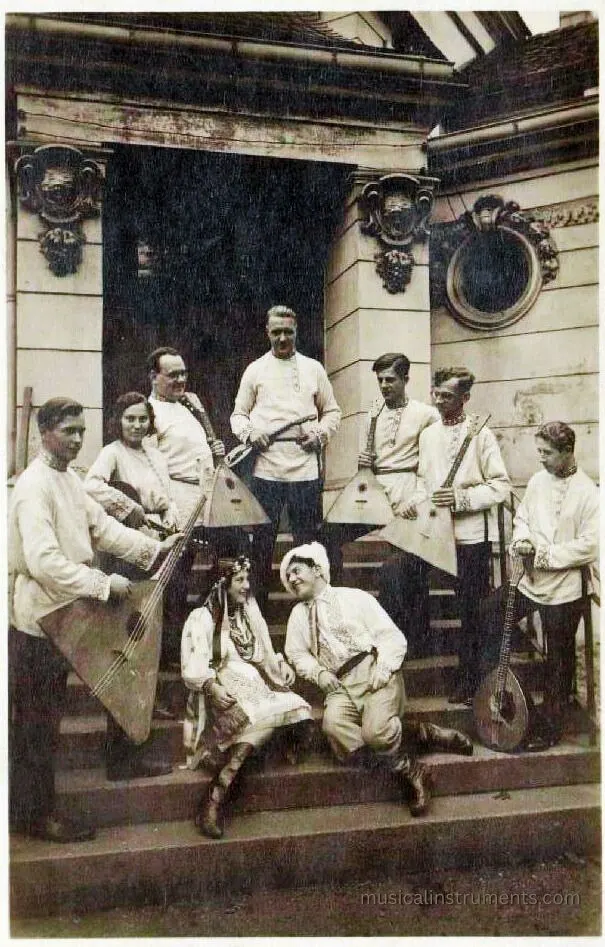

It used to live in the hands of village folk and street performers. Local people used to play simple songs heartly. Then a guy named Vasily Andreyev came along and turned it into something big. He made whole orchestras out of them. Suddenly, it went from backyards to big stages.

Now it’s more than just an instrument. It’s a piece of Russian heart. A sound full of story.If you’re curious, or just tired of the same old instruments, stick around. This Russian Instrument might just surprise you.

Where It All Began

It started in the Russian countryside, probably sometime in the 1600s. Back then, life was hard. People worked all day, and at night, they wanted music that felt like home.

So they built the balalaika.

It wasn’t perfect. Earlier they were rough and homemade, just a triangle of wood, a stick for a neck, and three strings made from animal gut or whatever they had around. But it worked. It sang.

Most folks who played it were poor. Farmers, wanderers, and skomorokhs kind of like street clowns or traveling performers would carry it around. They’d play songs, tell jokes, and share stories. The balalaika became a voice for people who didn’t always get heard.

But not everyone liked it.

The Orthodox Church wasn’t a fan. They thought the music was too wild, too joyful, too free. At one point, playing instruments like the balalaika was even banned. But that didn’t stop it. People kept playing anyway behind closed doors, around fires, in small village gatherings.

Then, in the late 1800s, Vasily Andreyev came along. He saw something special in this simple, joyful instrument. He cleaned up its design, gave it frets, made sure it could be tuned just right, and took it on tour. From tiny villages to packed theaters, he made people fall in love with it.

And just like that, the balalaika went from peasant street music to a proud piece of Russian culture.

Anatomy of the Balalaika

It’s not round like a banjo. Not wide like a guitar. It’s a triangle sharp, clean, and easy to spot from across the room. That triangular body isn’t just for looks. It gives the balalaika its crisp, punchy sound. When you hear that bright little “zing,” the shape is part of the reason.

The body is made from wood, usually spruce on top and maple or birch underneath. Light woods, but strong. They help the sound travel, even in big spaces. If you hold one, it’s not heavy. It sits easy in your lap, ready to go.

The neck is long, thin, with a flat face. Along the neck, you’ll see metal bars. These are frets, and they help players find the right notes fast. The balalaika has three strings, stretched from the base up to the top. Most of the time, those strings are tuned to E-E-A. It’s a tuning that sounds snappy and quick, kind of playful, but sharp too.

And depending on the size, the strings might be made from different stuff. Smaller ones use nylon or gut. Big ones, like the contrabass, use thick strings and even come with little legs to stand on the floor. Yes, some are that big.

So sure, it might seem like a simple triangle at first. But once you know the parts, you start to see what makes the balalaika so full of character.

Balalaika vs. Other String Instruments

| Instrument | Strings | Shape | Sound Style | Origin |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Balalaika | 3 | Triangle | Bright, snappy | Russia |

| Guitar | 6 | Hourglass | Smooth, warm | Spain |

| Banjo | 4 or 5 | Round body | Twangy, sharp | USA |

| Mandolin | 8 | Oval | Crisp, melodic | Italy |

The Balalaika Family

They come in different sizes, each one has its own voice. Some are high and sharp. Others are low and deep, like thunder. Together, they can play like a full band, all from the same shape, the same roots.

The smallest one is the piccolo. It’s tiny and light, and it plays the highest notes. Then there’s the prima balalaika, this is the one most people start with. It’s the most common, easy to carry, and super fun to play. A lot of solo music is written for this one.

Go a bit bigger and you’ll find the second and alto balalaikas. Their sound gets lower. They’re perfect for harmony, the “in-between” voices in a group.

Then we get to the big guys. The bass and contrabass balalaikas. These ones are huge. The contrabass is so big it has legs, like a little stool. You play it standing up or sitting down with it resting on the floor. And the sound? Deep, rich, and powerful.

When you gather all of them, you get a balalaika orchestra. Imagine a choir of triangles! Each size helps make the music. Some play the tune, some play the beat, and others play low sounds. Vasily Andreyev had a big dream. He wanted a whole team of balalaikas to play together, not just one.

So yeah, it’s not just one instrument. It’s a full voice range, from squeaky-high to floor-shaking low, all shaped like a slice of pie.

Types of Balalaikas

| Type | Size | Pitch | Common Use | Fun Fact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prima | Small | High | Melodies, solos | Most popular type |

| Sekunda | Medium | Mid-range | Harmony, rhythm | Adds depth to the melody |

| Alto | Larger | Lower mid | Background rhythm | Sounds like a soft hum |

| Bass | Big | Deep | Bassline, strong beats | Often played with a pick |

| Contrabass | Very large | Very deep | Ground-shaking notes | Played standing up like a bass |

How It Sounds and How It’s Played

The sound of balalaika is fast, bright, and full of energy. It’s not slow and dreamy like a cello. It’s not smooth and mellow like a saxophone. The balalaika has a zing. A snap. Sometimes even a little twang. It makes you want to move.

Most players use their fingers to pluck the strings, quick little flicks, almost like tapping. Some use a leather pick called a plectrum, especially on the big ones. Either way, the style is super active. You’re always moving, strumming, plucking, bouncing between rhythms and melodies.

And here’s the cool part: with just three strings, the balalaika can do a lot. It plays fast runs. It strums loud chords. It can even sound like it’s laughing. No kidding. That playful tone is part of what makes it so fun to listen to.

In groups, it sound even better. One plays the tune. Another adds rhythm. The big ones keep the beat, deep and strong.

Some people say the balalaika sounds like a mix of guitar, banjo, and mandolin. But really, it has its own voice. A voice with history. A voice with soul.

Vasily Andreyev’s Influence

Balalaika is from quiet Russian villages, where folks worked hard all day and played music to feel alive at night. It wasn’t fancy. It wasn’t taught in schools. But people loved it, they used it to dance, to sing, to tell stories. It was the heart of the party.

But then something big happened. In the late 1800s, a man named Vasily Andreyev heard it and thought, “Wait… this could be more.” He didn’t want to change it, just polish it a bit. So he redesigned it. Gave it frets, fixed the tuning, and made different sizes for different parts of music.

Then he started a balalaika orchestra, the first of its kind.

At first, people laughed. A full concert with just village triangles? But then they heard it. And the room went quiet. Then wild. People were amazed. The sound was rich. The energy was real. It wasn’t just folk music anymore, it was art.

Andreyev’s orchestra toured all over Russia, then to Europe, then the United States. The balalaika became more than a fun sound. It became a symbol of Russian culture. It showed that music didn’t have to be fancy to be powerful.

Today, you’ll still find balalaika players on street corners. But you’ll also see them in big halls, on world stages, even in film scores. Its voice bright, bold, and honest still connects.

A Sound That Travels: Global Reach and Modern Voices

The balalaika didn’t stay in Russia. It wandered, just like the people who first played it.

Now you can find it in places you wouldn’t expect. Washington, D.C., for example. Yep, right in the U.S. capital, there’s a whole balalaika society. They meet, rehearse, and perform like any orchestra, except it’s all balalaikas. Big ones. Small ones. All shapes, all voices.

And they’re not alone. There are balalaika groups in Japan, Europe, even Australia. People from totally different cultures have picked it up, learned to play, and made it part of their lives. That warm triangle sound? It travels.

But it’s not just groups. A few amazing solo players have pushed the balalaika into brand new places.

Take Alexey Arkhipovsky, for example. He’s not your average folk musician. He’s turned the balalaika into something wild, mixing classical, jazz, and even rock into one blazing, string-snapping show. You watch him play and think, “How is he doing that with just three strings?”

Alexey didn’t change the balalaika. He just opened it up. Showed what it could do. Now younger musicians are following him, remixing old village songs, mixing them with new beats, and finding their own sound.

The balalaika might be old. But it’s not done.

It still speaks. Still dances. Still finds new ears.

And if you’re listening, it might just find you too.

More Than Music: What the Balalaika Means

Balalaika is like the matryoshka doll, or the samovar in Russia. When people see it, they think “Russia.” But it’s not just about looks. It’s about what it stands for, joy, pride, and the spirit of everyday people.

For centuries, this three-string triangle has played behind stories of love, struggle, laughter, and hope. It grew from the ground up, not from kings or scholars, but from the hands of workers and dreamers. That’s why people feel something when they hear it. It’s music with roots.

You’ll see the balalaika everywhere, not just in concerts, but in films, books, and cartoons too. In old Soviet movies, it plays softly while someone remembers home. In spy films, it pops up to set the scene. Even when a character’s not holding one, the sound sneaks in like a quiet nod to where they come from.

Writers mention it when they want to show something real and raw. Artists paint it into village scenes. It shows up in everything from children’s tales to big, dramatic war stories.

It’s not trying to be fancy. It’s trying to be honest.

To Russians, the balalaika says, “This is who we are.” Not perfect. Not polished. But full of life.

FAQ

1. What is a balalaika?

It is a triangle-shaped string instrument from Russia. It has three strings and a wooden body. People play it with their fingers or a pick to make fast, bright sounds.

2. How do you pronounce balalaika?

It sounds like: bah-lah-LAI-kah. The middle part “lai” is said with a little rise, like singing.

3. Where did the balalaika come from?

It started in small Russian villages around the 1600s. Poor farmers and workers played it for fun. Later, it became popular across Russia

4. What is the balalaika made of?

Most of them are made from wood. The body is often spruce or fir, and the neck is birch or maple. The strings used to be made of gut, but now they are mostly metal or nylon.

5. Why does the balalaika have three strings?

The three-string design makes it simple to learn and play. It also gives fast and sharp sound. Some big balalaikas may have more strings, but three is the most common.

6. Is the balalaika still played today?

Yes! Many people still play it in Russia and other countries. There are even balalaika groups and orchestras around the world.

7. Is the balalaika only used in folk music?

Mostly, yes, but not always. Some modern artists use it in jazz, rock, or world music. It’s even been heard in movie soundtracks!

Final Thought: A Little Triangle, A Lot of Heart

Born in quiet villages, played by folks who worked hard all day and needed music that felt like home. Balalaika was never rich or fancy. But it had heart. Real heart.

Over time, it traveled, from campfires to big stages, from Russia to the rest of the world. It didn’t change much. Still the same triangle. Still the same three strings. But now more people hear it. And more people get it.

The balalaika doesn’t try to impress you. It just plays. And if you’re listening, really listening, it kind of sneaks into you.

You don’t have to be Russian. You don’t even have to be a musician. Just be someone who’s felt a little joy, a little ache, a little longing. That’s enough.

So if you ever come across this odd little instrument, don’t just look at it.

Sit with it. Listen.

It’s small, but it carries more than music.

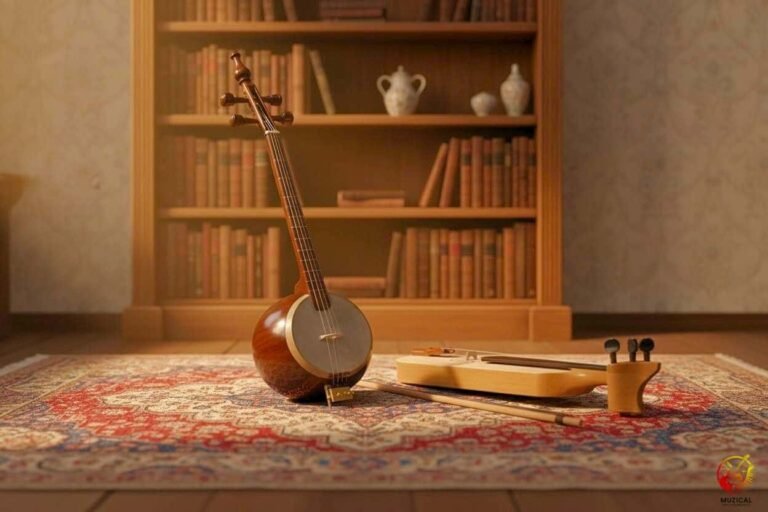

If you’re into folk string instruments, you might also enjoy learning about Kazakhstan’s traditional dombra, another powerful voice in Central Asian music.